Recalling my Father

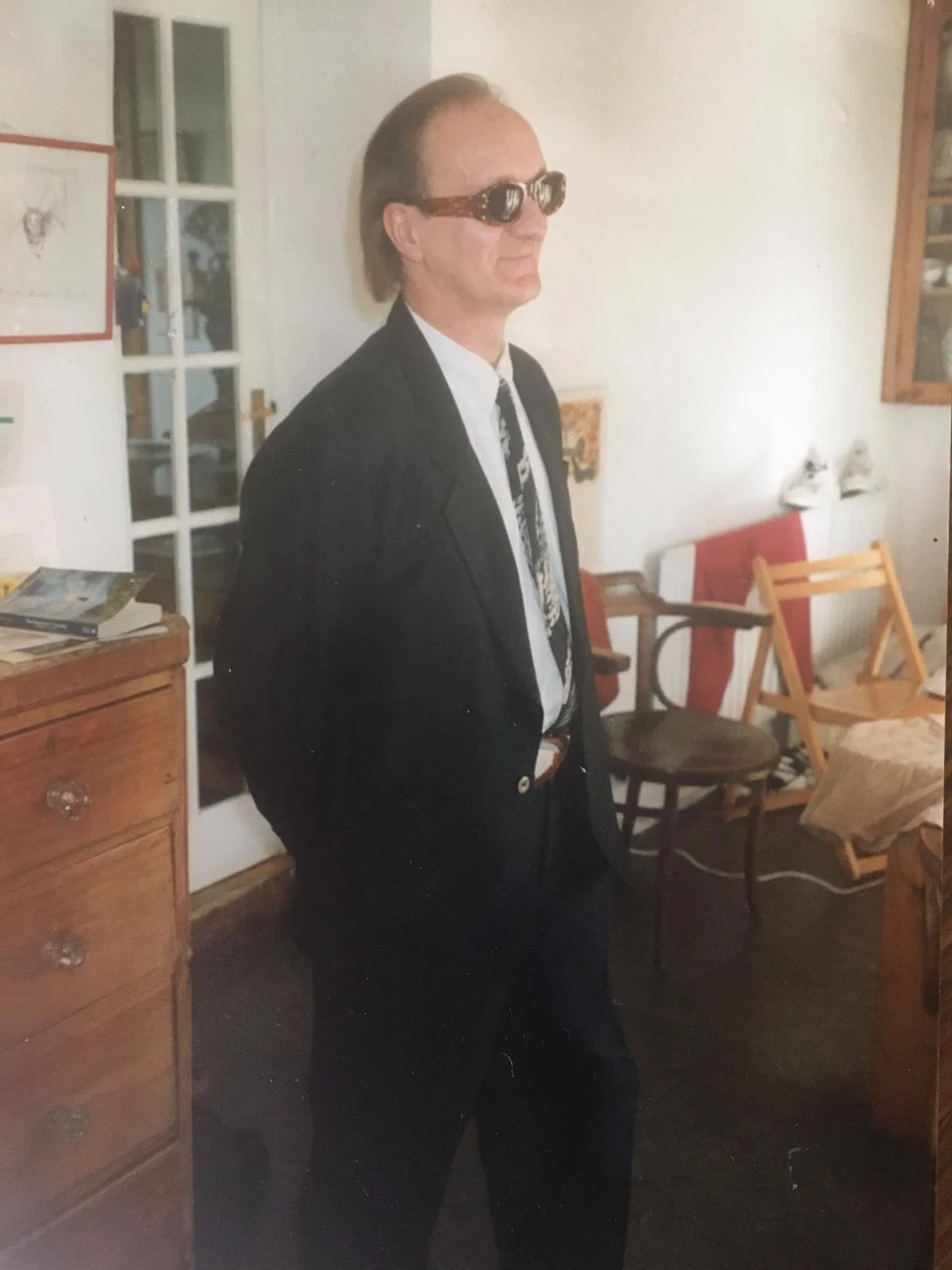

Image by Nick Wilkes, published with thanks

My father died twenty years ago to this day. For him, fittingly, an early adopter of all things alternative, experimental, transcendental and spiritual, he died on the summer solstice, aged 54. I am now just nine years younger than when he went and so as I edge closer to the full sum of his years on this planet, I am beginning to feel increasingly anxious about crossing the threshold of his final age, it feels somehow obscene to live past his age, yet it should be a cause for celebration.

Losing a dad young is something that many women of midlife share. Our fathers were one of the last generations to grow up in a fully unconscious health world, where smoking, drinking and living hard were esteemed, if not par for the course. My own dad started smoking at 10. It took 44 years to kill him, but it got there in the end. Men and fathers are conspicuously absent from my mothers 70-something year old demographic now, as so many never made it past 60.

So on Father’s Day, I am acutely aware that I am not alone in commemorating, at times cursing and also still trying to figure out a relationship that was stopped in its tracks.

When a parent dies young, you are denied that most golden of opportunities, an adult relationship with them.

Something that can often bear no resemblance to your childhood one. Fathers of Gen-Xers did not grow up in a time of enlightened parenthood either. My own dad was a highly enigmatic, intelligent, creative, elusive figure. The fact that I never really lived with him made our relationship all the harder to get a handle on. After my two sisters and I, which he had when married to our mum, he had two subsequent children with two other women, both of whom ended up cutting him out of their lives.

It was a complicated, seat of the pants life he lived. He craved attention and couldn’t handle real intimacy. An amazing thinker and polymath, he adored women and for most of his life pushed them away. Having three girls was in some ways a kind of irony as he was so ill-equipped to deal with the kind of fathering girls need. He pioneered music videos and children’s TV in Ireland, directing Anything Goes and promoting Irish music, and then moving to London to wrangle the likes of David Frost in the very first stages of early morning TV. He was roundly admired and also I think really misunderstood. He constantly suffered from imposter syndrome.

Jessie’s dad, Bob Collins.

He was the opposite of conventional when it came to parenting. When I was 17 on a visit from London, he waved me off happily as I went on a date with one of Prince’s touring dancers whom I’d met in Dublin. I barely knew the man’s second name. I think I had enough money for the Tube, maybe a taxi, I’m not even sure. At 18, he sent me off to Glastonbury where I’d arranged to meet friends somewhere in a field with a bunch of marijuana-infused cakes. He pretty much gave me my first joint. A workaholic, while also being a stoner, when I was 19, he gave myself and my sisters each a little mirror encrusted stash box with an eighth of hash in it at Christmas.

I knew something of who he was before he died, But actually I did most of the gleaning, and learning about him in the years subsequent to his death. It takes you to be a full grownup, to reconcile to who your parents really are. It is the relationship that lies beyond the dependence, the old habits, the cloud created by your need to be something for them. My relationship with my mother is unrecognisable in many ways to my early twenties. I was still under a kind of childhood jinx. And so was she. We communicate as equals now, and it is a rich experience.

My father, perhaps somewhat to his enjoyment, is never going to get old. But he is never going to experience that glorious, juicy later part of life. And when he learnt that himself, despite his hedonism, Buddhism, proselytising and philosophising, you could really see that regret coming over him.

You can throw all the theology at it you wanted, the truth is, you can never have enough time. You are never done.

What he ironically taught me through his own convoluted, inadvertent way, was to stick around as long as possible, to make it last.

Just before he died, we all gave up smoking, partly as solidarity with him, though terminally ill with lung cancer he never actually (in a final act of defiance he actually smuggled some grass into the hospice) but we all gave up almost as an arrow shot into the future. So perhaps one of my dads greatest gifts was to show me that, if you can reach for it, a long life matters. Life gets better, you get to refine it and most of the time, whenever your moment comes, you are only getting started. And though I missed out on many years, and a grown-up relationship with him, for that I am grateful

Jessie Collins, June 2020.

join the conversation

share and comment below, we’d love to hear your thoughts…